Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data is out this morning and the biggest news is in job openings. Since I’m on the west coast, everyone else was already up and ready to blog before me — and the narrative of “Fed actions finally hitting job openings” seems to have already solidified. However, a single data point doesn’t necessarily tell us much about the trend. It can, however, tell us about a discrepancy.

The seasonally adjusted data seemed to have been showing a bit of equilibrium trend (following the gray dotted line) for the past few months, but the latest data fell well below it:

This had created a theoretical puzzle for the dynamic information equilibrium model — there was no requirement for the data to return to the pre-2020 equilibrium and it seemed like there might be a equilibrating force (returning to a specific equilibrium) that doesn’t exist in the model (which only says it will return to some equilibrium). The latest data hasn’t completely eliminated that puzzle, but given the other series it’s not as glaring.

However, another puzzle it the recent data had created was a discrepancy with the seasonal adjustment — seasonally adjusted (SA) data had returned to an equilibrium but non-seasonally adjusted (NSA) data had not. Now both series are showing comparable trends with the latter being more uncertain due to higher noise:

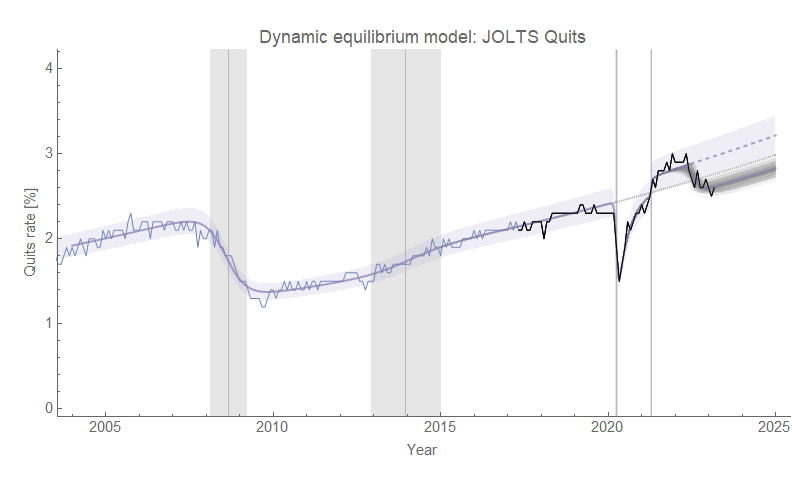

That said, there’s basically no change to quits or hires — both appear to have returned to an equilibrium (quits below the pre-2020 equilibrium and hires at1 the pre-2020 equilibrium):

Executive summary: not much change, but a couple of puzzles with the job openings data have become less perplexing.

PCE inflation data also came out last week and it’s showing the recent high core PCE data points were probably more noise than signal (but again, don’t put too much weight on a single data point):

And here’s year over year core PCE inflation. The model forecast will continue to undershoot for the next year due to the averaging in of the previous two months of data.

An update to the year-over-year forecast using the latest data shows the recent non-equilibrium shock widen by a few months:

I’ll continue to track using the December vintage data, however.

The puzzle was more that two of the three series seemed to be returning exactly to the pre-2020 equilibrium, but one out of three is more likely given measurement uncertainty.