Labor market update: 10 March 2023

JOLTS returning to equilibrium, unemployment still biased high

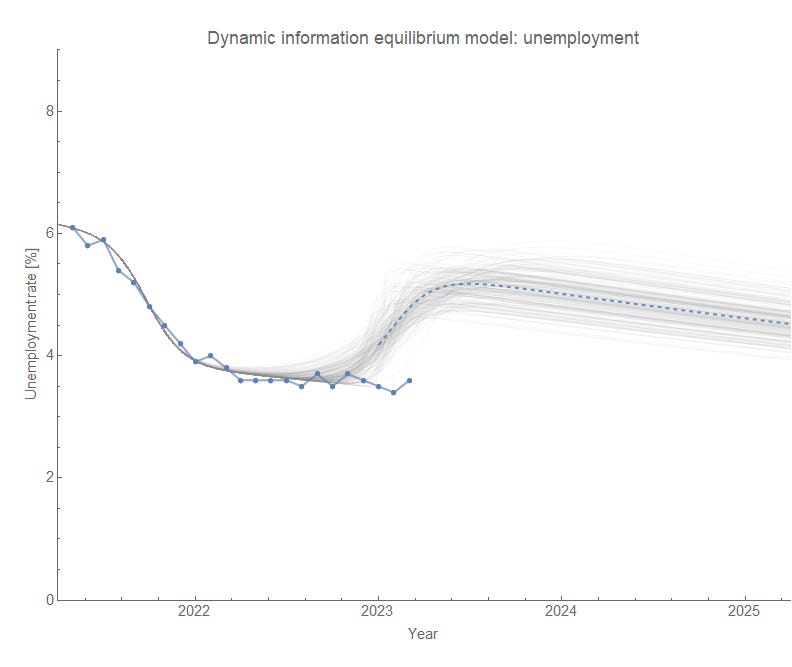

Sorry for the lack of blogging here — I’ve been nerding out on sci-fi world building lately. Anyway, the magic word for this post is “speculative”. The latest core1 unemployment rate data continues to be biased high2 hinting at an upcoming adverse shock. It’d still be delayed relative to the expected shock from hires (the speculative model, see below). Headline unemployment is also biased high relative to the model, but still isn’t as high as the Fed projections:

Initial claims (claims rate = initial claims per labor force size) still look like they are at the (speculative) noise floor:

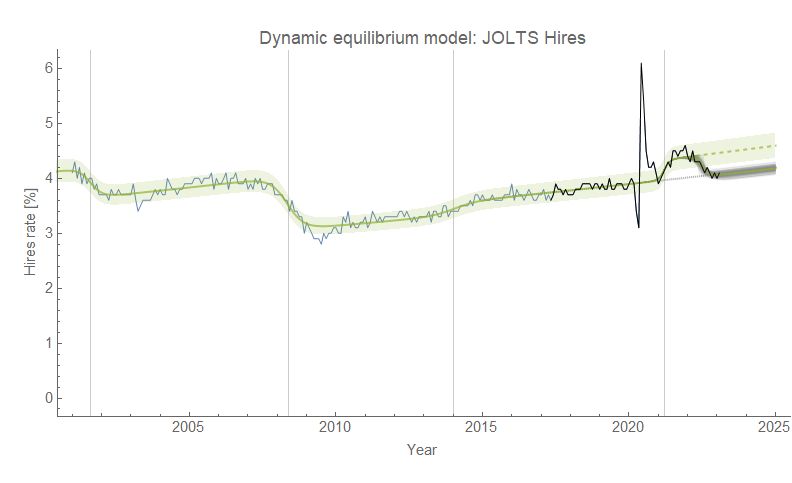

As for JOLTS that came out earlier this week, job openings appear to have returned to the pre-2020 equilibrium — I mean it’s almost exactly back on the gray dotted line below. Since the model does not enforce this kind of equilibrating forces (i.e. the negative shock at the pandemic, the positive stimulus, and subsequent negative “Fed” shock did not have to add up to zero), this seems to be either a coincidence or a hint at un-modeled dynamics.

Two caveats to that, however. One, if we remove seasonal adjustment, everything is far more uncertain — including the possibility that we’re even at a dynamic equilibrium3:

Two, quits has clearly fallen to an equilibrium below the pre-2020 equilibrium (and may still fall more):

The hires rate is showing the same return to the pre-2020 equilibrium that the job openings rate is showing:

Overall, this has been a “more of the same” employment report — not much additional information relative to the past few months. It still looks like the adverse shocks to JOLTS are ending and the adverse shock to unemployment is just hinting at getting started.

Speculative model forecast

Using the typical lag between shocks to hires and shocks to unemployment ~ 6 months and using the relative size based on the speculative model here, it appears the rise in unemployment is at best lagged relative to where it is expected in the graph above. One thing to note is that there aren’t many shocks to hires in the past data as narrow (short duration) as the one we’re currently experiencing — therefore (speculative²) if unemployment is slow to respond, the shock to unemployment could be much broader (longer duration) than the one to hires.

Wage growth is more consistent with the speculative model forecast:

Not sure where I mentioned it before (thought it was in last month’s update, but no), but there is a (speculative! drink!) mechanism for hires and wages to have a tighter link. Wage growth (ATL Fed wage growth tracker) for “job switchers” (see below) is much higher than for people who stay in a job. Therefore, if hires fall the mix of “stayers” and “switchers” becomes more biased towards “stayers” and the overall wage growth rate will drop. This could happen independently of the unemployment rate.

Again, speculative.

“Core” = U3 minus temporary layoffs (temporary layoffs spiked during COVID, but have more recently returned to the typical level relative to unemployment across the post-war period.

The original forecast from January 2022 (which had more uncertainty) is over a year old now and continues to be pretty accurate. The only issue I had with it that prompted me to make an update in August of 2022 was that missing the size of the stimulus shock (i.e. model guessed it was smaller than it turned out to be) meant that it would be more difficult to see a future rise in the unemployment rate.

Dynamic information equilibrium models (DIEMs) posit that economics equilibrium is a rate of growth (e.g. job openings) or decline (e.g. unemployment), not a level. For example, unemployment falling at (d/dt) log(u) ~ 0.09/y is the equilibrium.