Who should we listen to?

Scott Sumner asks the question, regarding macroeconomics: who should we listen to? He tries to suggest that we should assign a higher Bayesian prior probability to someone who has made several qualitative and ill-defined conditional predictions with a model only that person can use that are declared correct by the person who made them.

This is exactly who you shouldn't listen to.

You should assign a higher Bayesian prior to someone who makes quantitative predictions with well-defined conditions with a publicly available model that are declared correct by someone else.

What is particularly important is that other people can use the model. For example, the ITM equations and parameters are publicly available here:

http://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:arx:papers:1510.02435

Anyone can use them to make predictions or even build their own models.

No one can use Scott Sumner's model except Sumner himself. Here's his paper on monetary offset [pdf]. The model appears to be an AD-AS model, however the specifics depend on whether expansionary monetary policy is "effective", and there is no model of monetary policy effectiveness other than the ability to move exchange rates (#3, below), stock markets (#7, below) or successfully implement contractionary monetary policy (#8, below). So there is no evidence of effectiveness in terms of nominal (or real) output, the default metric of macroeconomics. These market moves also have not been large enough to be distinguished from noise (see e.g. here).

An additional issue is that Sumner does not describe how to produce counterfactuals with regards to monetary policy. We have no idea what would have happened in Sweden, the EU (#8, below), the US (#1, #2, and #4 below), Japan (#3, below) if monetary policy had been different. We must basically ask Scott if things would have been different, and if so, how different?

Sumner does not specify what the counterfactuals are with regards to fiscal policy (#2, below) and does not exactly specify exactly what constitutes fiscal policy. In fact, because it wasn't exactly specified there was a question as to whether dividends from GSEs constituted contractionary fiscal policy. Whether or not it does, this could not have been answered without hearing from Sumner -- again, we have to rely on Sumner himself to understand his model.

Sumner describes his model in terms of the "hot potato effect" and the "musical chairs model", neither of which contain any reference to productivity. Yet the Sumner's model has something to say about productivity (#9, below). How do we mere mortals extract this effect?

But Scott Sumner thinks we should listen to him. Well, we have to in order to know what his model says! Here's his list of predictions:

1. Those who, at the time, thought that Fed policy was too tight in late 2008 (something that Bernanke has now admitted).

What is "tight"? Who cares about a single opinion (Bernanke)? Do we know for a fact that tight monetary policy had any consequence in 2008? What is the counterfactual?

2. Those who correctly predicted that the contractionary effects of the 2013 fiscal cliff would be offset by monetary policy.

This one does not count.

We don't know the counterfactual (fiscal or monetary) here so there is no way to tell whether 2013 was more or less contractionary than the counterfactual. Most of the so-called contractionary fiscal policy was dividends from GSEs, so the actual deficit reduction was tiny compared to the noise in NGDP growth and therefore could not ever be empirically extracted from the data. The result was indeterminate.

3. Those who correctly predicted that the BOJ could sharply depreciate the yen, if they wanted to.

How can we tell if the BOJ "wants" to do something? Do moves in the exchange rate correspond to changes in NGDP? How do we convert "fall in exchange rate" to "rise in NGDP"?

4. Those who claimed Bernanke was wrong in claiming monetary policy was highly accommodative in the years after 2008. A critique that has now been confirmed by Vasco Curdia.)

What is the counterfactual? Would more accommodating monetary policy resulted in higher NGDP? No recession? We don't know.

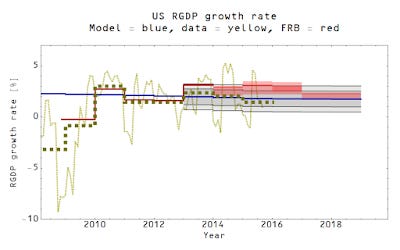

5. Those who said the Fed’s predictions for real GDP growth were too high.

How "high"? How is this discernible given noise and errors in the data? The Fed's predictions of RGDP are actually ok given the fluctuations in the measurements:

Also, I got these right -- shouldn't we listen to me?

6. Those who said that if we ended the extended unemployment benefits, the unemployment rate would fall back to the natural rate faster than the Fed expected. (Note this is the opposite of the previous prediction, which makes the success of both predictions especially interesting.)

This one also appears to be incorrect.

The acceleration in hiring appears to actually be the result of hiring in the health care industry due to the implementation of Obamacare because the increased rate of hiring is confined to the health care industry.

7. Those who first suggested that central banks could do negative IOR, and that markets would treat the policy as expansionary.

Did the markets move far enough to indicate something other than random noise? How big should the effect be?

8. Those who predicted that Trichet’s contractionary monetary policy of 2010-11, in response to transitory price rises from oil and VAT, was a big mistake. Ditto for those who made the same prediction about Sweden.

Is this a mistake? Do we know the counterfactual without the contractionary policy? No.

9. Those who first spotted the fact that the UK’s problem was productivity, not jobs, and hence that fiscal austerity was not the problem.

Sumner's model has inputs for productivity?

10. Those who predicted low interest rates as far as the eye can see.

What is "low"? "[A]s far as the eye can see" would be ok here (since it means indefinitely), but there is an implied conditional -- if the Fed creates an NGDP futures market and targets it, will rates rise? How far? What about a different policy? What will raise rates and by how much?