Unemployment ticks up

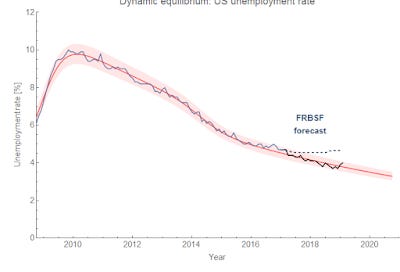

I think this is the longest I've gone without blogging since I started my blog! It's due to a confluence of factors — writing my second book (now about 1/2 written, and I'm learning so much finally looking at all these dynamic equilibrium models together from the 30,000 foot level), and I've become ridiculously busy at my real job. It means I missed the 2nd anniversary of the dynamic information equilibrium model. The model came out as a series of posts, first for JOLTS data (10 Jan 2017), then for the unemployment rate (11 Jan 2017), and finally a forecast of the unemployment rate (18 Jan 2017). That last forecast was compared with a forecast from the FRBSF that went until the end of 2018 — it was flat at about 4.7% the entire period. As I said in that last post:

The interesting thing is that in either [dynamic equilibrium] model we shouldn't expect the flattening out over the two year period [Dec 2016 to Dec 2018] we see in the FRBSF model. We should expect either 1) a recession to start raising unemployment, or 2) a continuing decline (albeit at a slower rate). A constant unemployment rate won't happen, and in fact generally doesn't happen [1]. We might be able to test the various models here [2].

And we could!

The uptick in the latest data to 4% is being blamed on the US government shutdown in the business news, but it's really well within the normal fluctuations of the unemployment rate so any speculation as to its cause is pretty much unfounded without detailed micro data. As a side note, there are various reasons why people think the Fed paused its rate increases at it's meeting this past week — discussed thoroughly by Frances Coppola here. However, I think Tim Duy has the best theory of the Fed's reaction function: as long as inflation isn't a problem, the Fed doesn't hike rates if unemployment is flat.

The most recent data shows a relatively flat unemployment rate for the past few months, much like in 2016. Basically, the FOMC has some model like the FRBSF model in its collective head of a constant equilibrium unemployment rate. And it's precisely that model which led the FRBSF forecast astray.