Interest rates and inflation

Apparently Randall Wray has set off the econ twitters with a pull quote captured here:

"There is no empirical evidence to support the belief that raising interest rates fights inflation."

It was pretty funny seeing the flurry of "obviously it does" countered with another flurry of studies of the lack of a connection or just various models (including DSGE models which are bad at forecasting) showing different results. I just found myself in a rare agreement with Wray. My own heterodox take — inflation is always and everywhere a labor force phenomenon — would probably be met with equivalent derision if anyone was paying attention.

My working hypothesis is two-fold:

When labor force participation is increasing faster than equilibrium (when women are entering the workforce in a demographic change or men entering the workforce after a war), we get a surge of inflation. When labor force participation declines, inflation flags.

When recessions happen during the a surge in labor force participation, it modulates that increase in participation causing oscillations — the Phillips curve. I have speculated that it is possible these processes are connected and that you always get "gravity waves" of inflation when labor force participation is increasing faster than equilibrium.

It is possible that the Fed triggers the recessions in the second part by raising rates instead of the oscillations being endogenous (i.e. generated by the surge process itself). In that sense, it is possible the Fed causes the recessions which cut off inflation. This would create a pattern of a series of Fed hikes before a recession which cuts off the inflation (and occurs near, but just after the peak). We'll call this A. However, if the Fed raising rates fights inflation, that should create a different pattern in the data: a surge in inflation should have started before the Fed starts hiking rates, and subsequently turnaround and end after or while the Fed is hiking rates — independent of a recession. This could also manifest as a fall in inflation. We'll call this B. Of course, there is also the possibility that Fed rates have nothing to do with the pattern of inflation (which is closer to my working hypothesis where the Phillips curve is endogenous). We'll call this C.

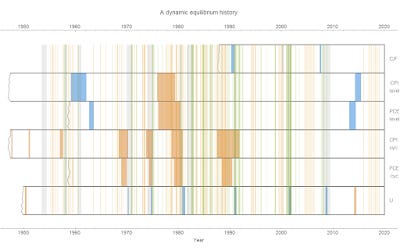

I will look at this through one of my "economic seismograms" that basically are a visual form of Granger causality (but a bit more conservative). I drew the changes in the time series with increases and decreases shown in red and blue (red is associated with economic growth, blue with decline/recession) and layered the Fed rate changes in yellow (raising rates) and green (lowering rates) as lines on top (click to enlarge):

What do we have? Well, in the period around 1960, we have a B — the Fed raised rates and what followed was a decline in inflation. You could possibly say that the '71, '74, and 80s recessions are A's.

In nearly every case though, the Fed's rate increases begin before the surges in inflation and end randomly relative to the turnaround point (the midpoint). It's almost the neo-Fisher hypothesis that Fed rate increases cause inflation! Recessions come at the tail end of these inflation surges as they're cut off by unemployment spikes, but sometimes we have no inflation surge (through most of the 90s and 00s). The Fed is always dutifully raising and lowering rates in sync with recessions. We even have an anti-B during the period of "lowflation" following the Great Recession — the Fed had lowered rates. That is to say most of the time we have C.

In fact, the single best explanation (we'll call it D) is that inflation and interest rates are unrelated but the Fed thinks it controls inflation and mitigates recessions with them, so it raises rates during economic expansion and lowers them after economic indicators turnaround before an oncoming recession. This has the benefit of the premise being incontrovertibly true — the FOMC does believe it can affect inflation or recessions with its rate choices.

I should always bring up Milton Friedman's thermostat here: if the Fed really did control inflation with policy, then it would look like there's no specific relationship between rates and inflation if they were doing it right. Of course this view is both question begging and unscientific in the sense that it shuts down inquiry. But a really good counter is that Fed policy is obviously correlated with recessions, so Occam's razor is that we should assume D until convincing evidence comes along to change our minds.