Against human-centric macroeconomics

"Gravity might not be explainable in terms of any broader, more general phenomenon. But we know for a fact that macroeconomics is the result of a whole bunch of little economic decisions by individuals and companies."

Do we really know this? For a fact? To be specific, I'm not questioning the idea that an economy is made up of humans making decisions with money (of course it is) -- I'm questioning the idea that observed macroeconomic relationships (price level and money supply, RGDP and employment) are the result of humans making decisions with money. This blog posits that macroeconomics is just about the large quantity of things (money, people in the labor force, goods and services) and human thought has a peripheral role. In that list we don't care what goods or money think, so why are humans so special?

I also have another question: is the idea of including human decision-making in economics a byproduct of our own human sense of agency rather than, say, solid reasoning or empirical justification? I think the answer is yes, it's a byproduct. Modern economics grew out of ethical philosophy and morality (it's all over everything: utilitarianism, the "Puritan work ethic" and macroeconomic "austerity", Adam Smith's The Moral Theory of Sentiments, the perceived morality of debt) and has therefore always been about human thought. It didn't grow out of natural philosophy (or science as it is known today) or accounting where it might have arisen from observation ("I noticed that everything seems to get more expensive on our books with each passing year, but also prices don't rise when business isn't good and we aren't hiring more people.").

In one of my early posts, I mention that my approach to economics has been that of an alien observer who has good enough instruments to see how nighttime lights are increasing and CO2 is increasing on Earth, land is cleared and posits the idea of a "civilization" on Earth that operates under a theory of "economics" ... analogous to Boltzmann positing atoms operating under a theory of statistical mechanics.

Macroeconomics does not take this approach, but instead started at the very beginning assuming that human behavior was important. Modern economics has some of its origins in physiocracy, and in that economic theory sits the 17th century analog of expectations (quoting from wikipedia, emphasis mine):

Pierre Le Pesant ... advocated less government interference in the grain market, as any such interference would generate "anticipations" which would prevent the policy from working. For instance, if the government bought corn abroad, some people would speculate that there is likely to be a shortage and would buy more corn, leading to higher prices and more of a shortage.

and incentives:

Le Pesant asserted that wealth came from self-interest and markets are connected by money flows (i.e. an expense for the buyer is revenue for the producer). Thus he realized that lowering prices in times of shortage – common at the time – is dangerous economically as it acted as a disincentive to production.

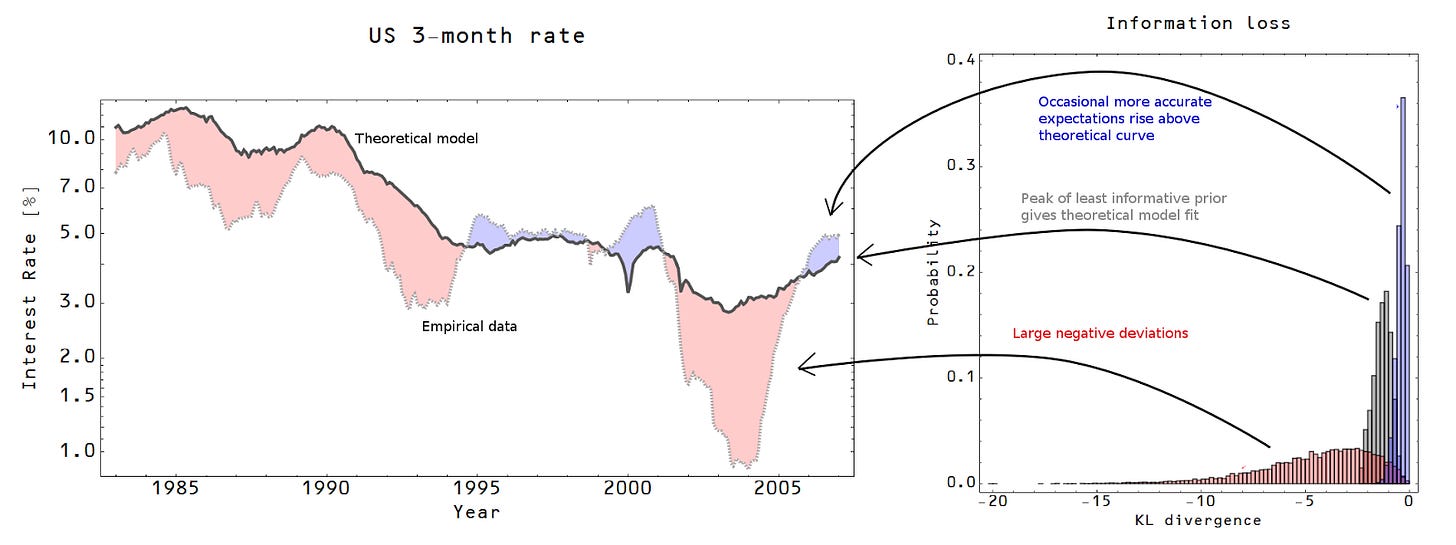

All that can be said (from the information-theoretic point of view) is that a price control changes the information transfer capacity of a particular channel detected by that price (relative to other channels). An incentive (i.e. the knowledge people are willing to pay way more for your goods and/or services than it costs to produce them) is just one piece of information transferred from demand to supply. So is irrational fear. So are speculative hedges ("I may pay top dollar for your goods now, but by the time you build the capacity, I won't"). So is random lack of knowledge ("I guess bacon just costs 50 dollars per pound"). The correctness (or content) of these ideas are not (to first order) important. This was part of the revolution of information theory (see the overview at that link) -- the human meaning of the message is irrelevant. It may be that human thought is very important to a description deviations from the underlying trend:

But in not looking at a human-independent baseline, we don't really know what the real economic fluctuations are (see here and here). Have we been led astray because we as humans were too close to the problem?

Tom Brown asks in a comment (that I can't seem to find right now, update: Tom found it, thanks!) if the information transfer model would apply to non-human economies. I don't know the answer to that. However, macroeconomics as conducted today has an answer: no, it doesn't apply. There are no economic laws that are independent of human thought. Even supply curves depend on expectations of future prices and demand curves depend on consumers' tastes and preferences (and diminishing marginal utility). Recessions might not happen among Klingons and the Ferengi Phillips curve might be perfectly stable. It would be an act of hubris to think an alien civilization thinks the same way we do ... e.g. would risk premia be the same? Some economists do this already with different human cultures, and I touched on it in an earlier post. Maybe this is the correct approach. If it is, then economists should completely abandon any pretense to universality and instead become a sub-discipline of history (the chapter on the period when economists thought universal laws existed would be entertaining).

I believe there is at least a major component that is independent of human behavior, not only because of the successes of the information transfer model but because one of the most successful economic predictions ever assumed that human behavior, on average, summed up to noise:

Suppose that there are a whole ton of different behavioral biases, and that these vary across time, across people, and across situations so much that even with a billion lab experiments we couldn't find them all. Only once in a while will the forces be aligned to make one behavioral bias dominate; most of the time, the net effect of all the biases will be unpredictable by the outside observer. When you have an unpredictable mishmash like that, you have to model it as a stochastic process. In other words, if it's too complicated to explain deterministically, then you treat it as randomness.

So what if psychology usually just ends up injecting randomness into our decisions?

That was from Noah Smith again. It is exactly the theory behind information transfer economics.

PS (added 8/4/2014, 9:28pm MDT): The thrust of this post is opposition to human-centric macro, and not saying human behavior has no role whatsoever (the third sentence says "of course" an economy is made of people, the graph in the middle is quite literally me calculating the impact of expectations, and I kept the piece of the quote of Noah's post that says "once in a while will the forces be aligned to make one behavioral bias dominate").